Talk:Modular equivalence: Difference between revisions

m (Alternate Mod Notation) |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

[[File:Modexamples.png|left|alt=Alternate mod notation as rendered in Latex|Alternate mod notation as rendered in Latex]] | [[File:Modexamples.png|left|alt=Alternate mod notation as rendered in Latex|Alternate mod notation as rendered in Latex]] | ||

<hr/> | |||

Would \(7 \underset{3}{=} 1\) work similarly? | |||

--[[User:Christian Lawson-Perfect|Christian Lawson-Perfect]] ([[User talk:Christian Lawson-Perfect|talk]]) 15:06, 10 July 2021 (UTC) | |||

Revision as of 15:06, 10 July 2021

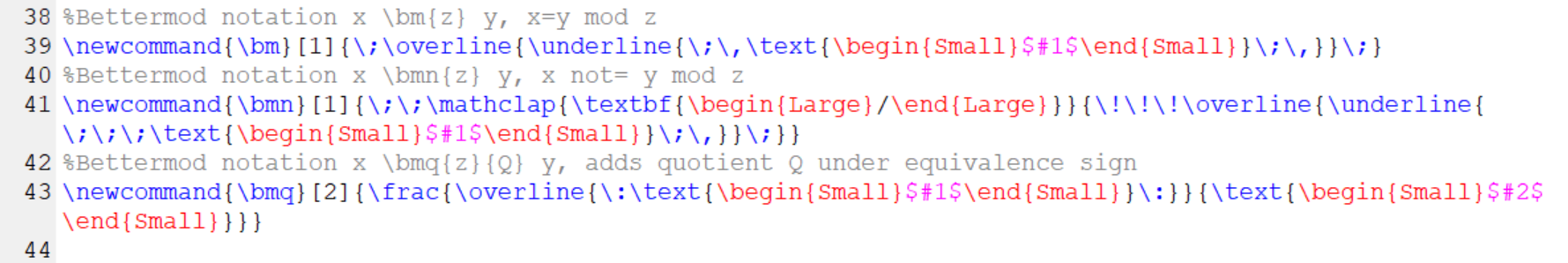

Mod notation can be bulky and counter-intuitive. Here is an alternate mod notation that simply removes the middle line from the equivalence sign, places the modulus inside and drops the now moot 'mod'.

The following macros are defined for the Latex that follows and the second graphic shows the result:

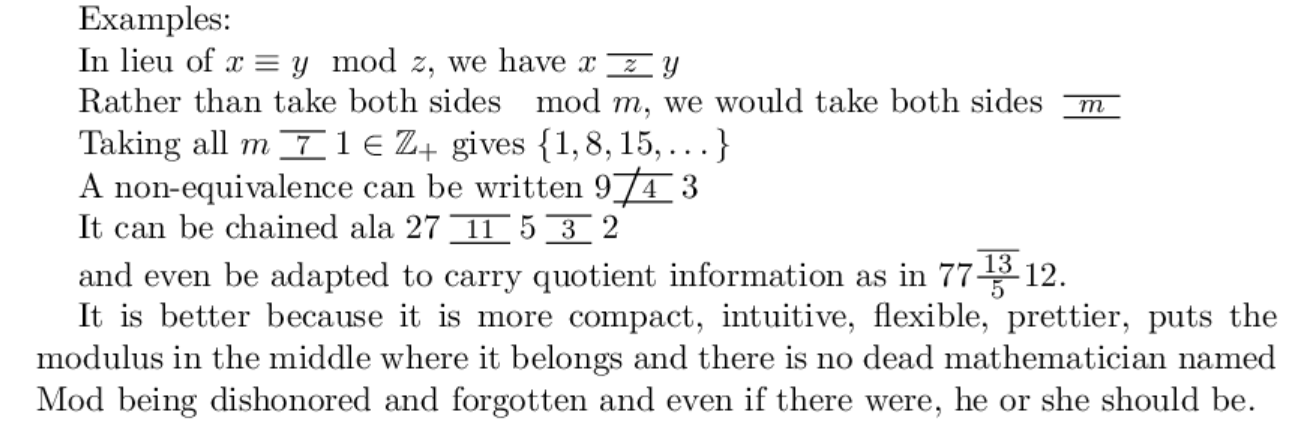

Examples: In lieu of $x\equiv y \mod{z}$, we have $x\bm{z}y$

Rather than take both sides $\mod{m}$, we would take both sides $\bm{m}$

Taking all $m\bm{7}1\in \mathbb{Z}_{+}$ gives $\{1,8,15,\dots\}$

A non-equivalence can be written $9\bmn{4}3$

It can be chained ala $27\bm{11}5\bm{3}2$

and even be adapted to carry quotient information as in $77\bmq{13}{5}12$.

Here's how that looks when rendered:

Would \(7 \underset{3}{=} 1\) work similarly?

--Christian Lawson-Perfect (talk) 15:06, 10 July 2021 (UTC)